What’s in a name?

By Milena Marinkova and Milada Walková

Deborah Cameron (2021) discusses referencing sources from a feminist perspective. On the one hand, gender identity of female academics becomes hidden in citations by default (as in Cameron, 2021) and in references when only initials but not full first names are given (as in Cameron, D. 2021.), she argues. On the other hand, obscuring gender identity might work in women’s favour, as has been seen in creative writing (a well-known example being J.K. Rowling). But is this always the case? Many Slavic women are stripped of the possibility to conceal their gender by using their surname only. The reason is that in several Slavic languages female surnames are grammatically marked for gender as they include a feminine suffix such as –a/-á or -ova/-ová (e.g., masculine Zelensky, Kováč – feminine Zelenska, Kováčová).

Slavic surnames, however, reveal not only gender, but also cultural (national, linguistic) identity. Having separate masculine and feminine forms of surname is common across several Slavic languages – including Czech, Russian and Bulgarian, among others.

And yet, in non-Slavic speaking contexts those having surnames ending in -ova tend to be lumped together into one homogenous group – read “Eastern European” – as exemplified in the disparaging comment by Serena Williams and news coverage during the 2009 US Open: “All these new -ovas. I don’t really know anyone. I don’t really recognise anyone. That’s just how it is. I think my name must be Williamsova." (The Times, 2009). The suffix -ova here seems to signify difference, an otherness, something that cannot be fully known and something that takes the Anglophone reader / listener out of their comfort zone, disrupting the familiar flow of sounds and rhythms. At the same time, there is sufficient awareness of the suffix for the Anglophone self to create a mental map that both over-defines such -ovas by slotting them into a pre-determined cultural identity and strips them of any individual qualities: a form of Cold War othering that establishes a false dichotomy between a uniform “West” and homogenous “East”, and splits “Europe” along civilizational lines into two distinct “discourse-geographies” (Bjelić and Savić, 2005; Wolff, 1994).

And yet, in non-Slavic speaking contexts those having surnames ending in -ova tend to be lumped together into one homogenous group – read “Eastern European” – as exemplified in the disparaging comment by Serena Williams and news coverage during the 2009 US Open: “All these new -ovas. I don’t really know anyone. I don’t really recognise anyone. That’s just how it is. I think my name must be Williamsova." (The Times, 2009). The suffix -ova here seems to signify difference, an otherness, something that cannot be fully known and something that takes the Anglophone reader / listener out of their comfort zone, disrupting the familiar flow of sounds and rhythms. At the same time, there is sufficient awareness of the suffix for the Anglophone self to create a mental map that both over-defines such -ovas by slotting them into a pre-determined cultural identity and strips them of any individual qualities: a form of Cold War othering that establishes a false dichotomy between a uniform “West” and homogenous “East”, and splits “Europe” along civilizational lines into two distinct “discourse-geographies” (Bjelić and Savić, 2005; Wolff, 1994).

The simultaneous over-determination and effacement of identity via names is not just present in sports and media, but also in other walks of life, including academia. Universities in the Anglophone world of the geopolitical “West” have been on their internationalisation journeys for well over a decade now, with mission statements inevitably celebrating their diverse make-up, global outlook and inclusive values. More recently, in the UK HEI context and more specifically at Leeds University, there has been a concerted drive towards a plethora of worthwhile initiatives about making a difference in a global world and building an “international mindset” in the academic community; achieving equality, inclusion and social justice at all stages of a student’s journey; and facilitating student and staff sense of belonging through curriculum and pedagogical innovation. The sheer volume and interminable flow of mission statements, strategy documents and guidance manuals, however, risks overwhelming the intended audience and turning the laudable values of equality, inclusion and diversity into trendy buzzwords, empty of meaningful content or practical application. And thus international students and scholars, and a range of marginalised groups, risk becoming but only a statistic on the Equality and Inclusion Unit pages (for whatever purpose, be it to celebrate diversity of staff and students, or to question the representation and treatment of individuals and groups perceived as different). This is why perhaps one way in which we can start conceptualising the meaning of difference that takes into account the uniqueness of individuals and recognises the intersectionality of identity, that is cognisant of challenges encountered by specific groups whilst also acknowledging the diversity of stories and voices within communities, is through careful and considerate engagement with names, as the first tip on this page about developing a sense of belonging suggests.

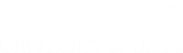

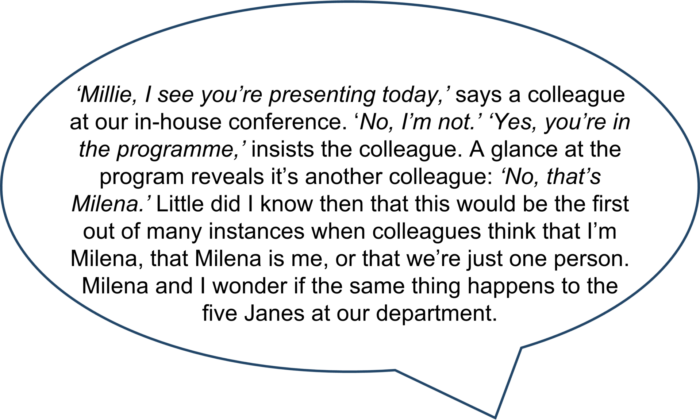

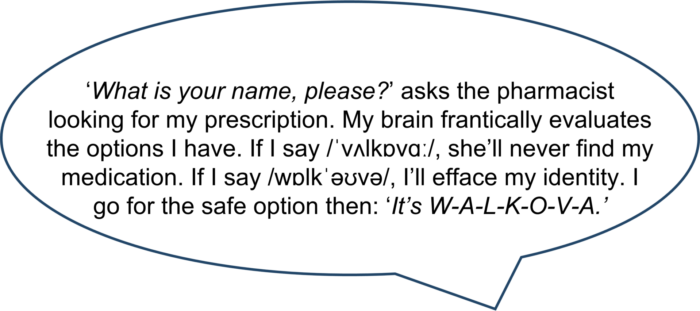

As we’ve learnt from J. L Austin (1962), naming (i.e., the acts of giving someone a name, addressing someone or even calling someone names) is a speech act that does more than merely refer to or describe someone. The act of naming does something to all participants in the communicative situation. On the one hand, for those being addressed, the act has the “performative effect of having been named as this gender or another gender, as part of one nationality or a minority, or … how you are regarded in any of these respects” (Butler, 2016, p.16). In our case, it is important to reflect on what it might mean for someone – say, an international

student or scholar at a UK HEI – to be mis/named, more often than not without their consent or awareness. What attitudes towards themselves would this individual imagine if their name becomes an apology-prefaced, unrecognizable scrawl or an indigestible mouthful? How felicitous would such an utterance be (in Austin’s terms) if the individual cannot recognise themselves in the name by which they are called? Or worse still, when their stumbling block of a name becomes interchangeable with the names of those others who are similarly (ethnically, linguistically, religiously, or sexually) different? And would the frequently repeated “I’m not sure whether I’m pronouncing this correctly…” – either as an apology or as a self-denigratory joke – be indicative of a speaker’s inability to shape their mouth, twist their tongue or modulate their tone to say a name, or perhaps gesture at something more pernicious – a refusal to learn, a joke that is not that funny the fifth time around, an apology that comments on “difference” as unassimilable?

student or scholar at a UK HEI – to be mis/named, more often than not without their consent or awareness. What attitudes towards themselves would this individual imagine if their name becomes an apology-prefaced, unrecognizable scrawl or an indigestible mouthful? How felicitous would such an utterance be (in Austin’s terms) if the individual cannot recognise themselves in the name by which they are called? Or worse still, when their stumbling block of a name becomes interchangeable with the names of those others who are similarly (ethnically, linguistically, religiously, or sexually) different? And would the frequently repeated “I’m not sure whether I’m pronouncing this correctly…” – either as an apology or as a self-denigratory joke – be indicative of a speaker’s inability to shape their mouth, twist their tongue or modulate their tone to say a name, or perhaps gesture at something more pernicious – a refusal to learn, a joke that is not that funny the fifth time around, an apology that comments on “difference” as unassimilable?

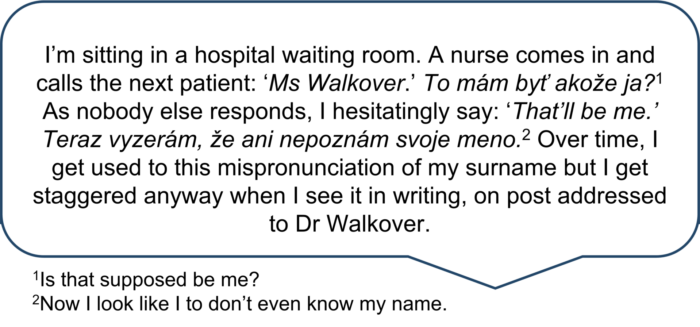

On the other hand, as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (2002) has argued, the performativity of language can open up alternative spaces for identity choices that are at odds with dominant norms. Faced by individual, and often, institutional and social reluctance to process the foreignness of their names, some students and scholars would opt for more “accessible” aliases in the dominant language that might bear an aural or semantic semblance to their original names, or would riff-off playfully with an Anglicised misnomer / mispronunciation, or just take advantage of the general unrecognizability of their names and create a new name that might be deviating from established norms (here or elsewhere).

An instance of practical translation or a playful appropriation of the dominant code, such a performative might be agentive – so that those previously lumped into an unrecognisable mess of random sounds / letters can have some kind of public recognition as individuals, or even claim control over the dominant linguistic tools in order to mis/name themselves on their own terms. What this might mean for us as educators is to be acutely aware of the performative effects of mis/naming and embark on what bell hooks has called “engaged pedagogy” (1994): a holistic practice which construes learners as “whole human beings with complex lives and experiences rather than simply as seekers after compartmentalized bits of knowledge” (p.15). Fundamental to such a model is the creation of “a community of practice” (Lave and Wenger, 1991), where each voice is seen, heard and respected as an individual rather than as a marker of difference. Such a community, along the lines of Adrian Holliday’s notion of “small culture” (1999) should cohere around a common goal or social process (e.g., that of learning), and it should create the space for its members to bring in individual and/or collective identity positions, experiences and histories, without being defined by them. And the starting point of such a community should be the recognition of the unique sounds, shapes, meanings and histories of the diverse names in our classrooms.

This may not be an easy or pain-free experience; there might be false starts and errors, and initial apologies might not be totally amiss. But similar to the often-tortuous detours and unlearning that we expect students on pre- and in-sessional EAP (English for Academic Purposes) courses to undertake (take your pick, from paraphrasing of sources to the use of the first-person in academic writing), it might be necessary that we, the educators, unlearn familiar practices of “dealing” with unfamiliar names (e.g., anglicising, apologising, misnaming). Apologies can go only so far and at some point, we’ll have to weave our professed ideas of inclusion into our pedagogical “habits of being”. Anglicised nicknames might be adopted as a self-fashioning strategy in a new educational context, but this should be the name bearers’ choice rather than a discourse imposed on them. As hooks concludes (incidentally, herself an example of someone opting for a new name), discomfort in unlearning is an important shared experience: “[T]here can be, and usually is, some degree of pain involved in giving up old ways of thinking and knowing and learning new approaches. I respect that pain. And I include recognition of it now when I teach […] This gives [students] both the opportunity to know that difficult experiences may be common and practice at integrating theory and practice: ways of knowing with habits of being... Through this process we build community.” (1994, pp.42-3)

The process of unlearning, or what Erica McWilliam (2008) has also referred to as adopting an “error welcoming” pedagogy and “the disposition to be usefully ignorant” (p.266), will inevitably be accompanied by that of learning… together. For not unlike the collaborative knowledge construction taking place in the EAP classroom where we – as English language experts and pedagogues – work together with our students – as subject experts and expert users in at least one language – to identify and operationalise discipline-specific epistemologies and discourses (Hyland, 2018), when it comes to the culturally inflected and personally meaningful

experiences of mis/naming we should be prepared to trust our students, learn from their expertise and avoid being defensive due to perceived vulnerability in our own knowledge. Learning with/from our students is enriching: we “can do this without negating the position of authority professors have, since fundamentally […]combining the analytical and experiential is a richer way of knowing” (hooks, 1994, p.89). At the same time, as scholars such as Martha Fineman (2014) and Judith Butler (2016), among others, have suggested the concept of vulnerability needn’t be associated with the dependency, fragility and weakness of designated at-risk groups or individuals, but can be agentive and indicative of “a broader [human] condition of … interdependency” (Butler, 2016, p.21), ethical responsiveness to others and awareness of knowledge as “not fully masterable” by the self (p.25).

experiences of mis/naming we should be prepared to trust our students, learn from their expertise and avoid being defensive due to perceived vulnerability in our own knowledge. Learning with/from our students is enriching: we “can do this without negating the position of authority professors have, since fundamentally […]combining the analytical and experiential is a richer way of knowing” (hooks, 1994, p.89). At the same time, as scholars such as Martha Fineman (2014) and Judith Butler (2016), among others, have suggested the concept of vulnerability needn’t be associated with the dependency, fragility and weakness of designated at-risk groups or individuals, but can be agentive and indicative of “a broader [human] condition of … interdependency” (Butler, 2016, p.21), ethical responsiveness to others and awareness of knowledge as “not fully masterable” by the self (p.25).

References:

Austin, J.L. 1962. How to do things with words. Ed. by J. O. Urmson and Marina Sbisá. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

Bjelić, D. I. and Savić, O. 2005. Balkan as metaphor: between globalization and fragmentation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Butler, J. 2016. Rethinking vulnerability and resistance. In: Butler, J. Gambetti, Z. and Sabsay, L. Eds. Vulnerability in resistance. Durham, NC: Duke UP, pp.12-27.

Cameron, D. 2021. Women of letters. [Online]. [Accessed 21 March 2022]. Available from: https://debuk.wordpress.com/

Fineman, M. 2014. Vulnerability and the human condition initiative. [Online]. [Accessed 16 March 2022]. Available from: https://web.gs.emory.edu.

Holliday, A. 1999. Small cultures. Applied Linguistics. 20 (2), pp.237–264.

hooks, b. 1994. Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom. New York and London: Routledge.

Hutt, D. 2021. Why some Czechs are up in arms ova plans to drop feminised surnames. Euronews. [Online]. [Accessed 24 March 2022]. Available from: https://www.euronews.com/.

Hyland, K. 2018. Sympathy for the devil? A defence of EAP. Language Teaching. 51 (3), pp.383–399.

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

McWilliam, E. 2008. Unlearning how to teach. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. 45 (3), pp.263–269.

Mott, S. 2009. They think it’s all Ova: women’s tennis is being overrun by an army of anonymous blonde Russians with something in common – freezing in big finals. The Times. [Online]. [Accessed 25 January 2022]. Available from: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/.

Sedgwick, E. K. 2002. Touching, feeling: affect, pedagogy, performativity. Durham, NC: Duke UP.

Wolff, L. 1994. Inventing Eastern Europe: the map of civilization on the mind of the Enlightenment. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP.